|

|

|

|

| Erasmus

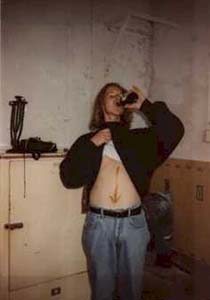

Art Exchange project, Art Center Leiden 1995 |

Randolf's

& Nanda's Wedding, Polder leiden 2000 |

Beijing, 2004 | Shanghai, 2006 |

A Singular Eye 1968 was a tumultuous year, marked by war and political turmoil. It was also a productive year for the parents of Randolf Bruin. By the time the calendar switched to 69, they had issued forth the man who would be responsible for the paintings you will see today. Not an artist in the romanticized, traditional sense of a tortured soul that wracks the world with the reflections of his disturbed psyche, but in the joyous sense, Randolf celebrates form and color with the courage of a child, plucking inspiration from both the mundane and the sublime, and blending them into works that are at once titillating fantasies and social commentary. Since, picking up the knife at 19 (a palette knife that was), Randolf has been merrily slashing through preconceptions and tired social mores with gleeful abandon. In 1987, he was busily subjecting himself to feeble attempts at indoctrination, by the dogs of academia. Psychology. Industrial design. Fall in line. Goose-step to the finish where you will receive a small piece of parchment indicating that you fit snugly into a well-defined box. For Randolf, though, that closed box never had much appeal. Instead the sweat and churn of the bars in Leiden were the flavors that stimulated his palette. So he readily immersed himself in this new, fascinating opportunity (not found, but created) to give shape and expression to the denizens of his youthful world. Some men take instruction well. Some are well read. Then there are those, like Randolf who are students of life. Without formal training, and consequently without the artificial constraints of tradition, he set about articulating both his own personal vision, unique to his eye, and the various scenes that crossed it. Having abandoned academia, he collaborated with artists in the city to establish the “X” Exhibition Hall in Leiden, where he held several exhibitions of his own work along with more than 25 exhibitions of other artists. In cooperation with several of these artists he then helped found the “De Leidse School”, which thrives today, providing studio space for more than 50 artists in Leiden. Although clearly an inspiration in his early work, Leiden was never going to be sufficient for a man seeking beauty and diversity in the female form. As a non-traditionalist with a mischievous streak, Randolf had set his sights squarely on one of the bastions of traditional art, the female nude. The results were indeed striking, as Randolf utilized uncommon forms and framings that defied convention, and spiced his work with colors that evoked salacious hallucinations. All the while, he still managed to capture the ephemeral thrill of stolen movement. While on holiday in China during the summer of 1997, Randolf met the Chinese painter, Wang Yang at his studio in Wuxi. Wang later helped Randolf stage his first Asian exhibition, in December 1998 at the invitation of the Wuxi City Artists’ Association. Having found his voice and his muse, Randolf decided to pursue his expression in this new, provocative context that was China and moved to Guangzhou.

|

At the time, China was a hotbed of change, where young artists, indeed young people of all walks of life, were challenging centuries of tradition and long established modes of expression were breaking down. In short, it was an ideal crucible in which the young Bruin could refine his approach. In his work from the Guangzhou period, he continues to test the bounds of traditional expression, and he occasionally found himself testing the boundaries of a very different society as well. His work was well-received by young, inquisitive urbanites in the fast-moving southern Chinese city, as much for its boldness as for its subject matter. During his time in Guangzhou, he held numerous exhibitions at galleries around town, including one opened by the Dutch Consul-General at the Persimmon Art Gallery. In 2001, Randolf relocated from Guangzhou to Beijing, to be closer to the nucleus of China’s political transformation. With its vibrant art scene and equally vibrant night-life, he has never been at a loss for inspiration and opportunity since the move. Intrigued by the elusively, basic forms of everyday articles, and their emotional impact, he began incorporating them into many of his works. He had first explored this technique in the Netherlands, but now took it up with more vigor and purpose, using posters, brooms, charcoal and other artifacts that held significance in contemporary China. By juxtaposing these with his own unique representations of the female form, he skillfully struck a balance between the universally recognized beauty of the female form and the chaos of everyday flotsam. By 2003, Randolf’s fascination with the female form had produced an even more striking result, namely Quin Gandalf Griffioen, whose earliest works are also displayed here. True to his father’s tradition, Quin has a natural affinity for the female form, is completely self-taught and is not bound by traditional or academic attitudes about what art should be. In fact, it is highly unlikely that he has opened a book on art, except perhaps, in order to tear out a few pages. And so, a tradition continues, passed down through their DNA and nurtured in the context of a Chinese landscape that is changing under their very feet. Today, Randolf Bruin continues to defy convention, keeping a watchful and ever-playful eye on the changing forms of contemporary China. As he experiments with mixed media and new modes of expression, his work has matured. Discarded articles become artifacts, challenging our assumptions about value and casting light on the fast-disappearing and under-acknowledged trappings of China’s past. Forms and movement in his work have become more abstract and expressive, while shading and color challenge the eye to view bodies in new ways. Currently, Randolf’s work is on permanent exhibit at the Hidden Tree, a Belgian bar in Beijing. |

|